<<<Back to Part 2

#11 Foucault saw Deleuze as a rival

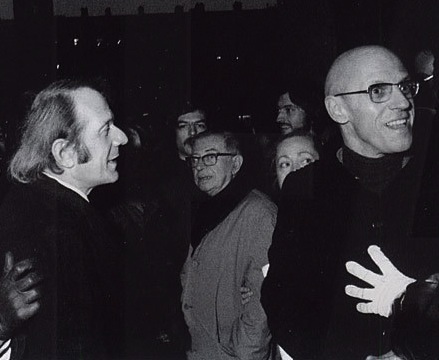

Some may find it surprising that the author of “Anti-Oedipus'” glowing introduction kind of hated the book. While Michel Foucault put on airs of amicability towards Deleuze, he was secretly jealous of Deleuze’s popularity. A close friend of Foucault’s claimed “I got the feeling that Foucault saw Deleuze as a rival.”

The rivalry rarely manifested publicly, Deleuze and Foucault could often be seen at public protests together, and Foucault even offered Deleuze a job in his philosophy department (which Deleuze had to initially refuse due to a prior commitment). Foucault even join the ranks of Nietzsche and Spinoza when Deleuze wrote “Foucault.”

Only once did Deleuze unknowingly go too far for Foucault. Deleuze had offered to write the preface to Jacques Donzelot’s thesis on “Policing the Family.” This, by the way, is the thesis that Deleuze helped Donzelot defend when he got stage fright. When Donzelot told Foucault the news, Foucault remarked “I detest that sort of thing. I can’t stand it when old men come and put their stamp on young people’s work.”

And despite the glowing introduction Foucault wrote for “Anti-Oedipus,” he allegedly hated it. Donzelot, who was a close friend of Foucault, stated “Foucault didn’t like Anti-Oedipus and told me so quite often.”

When Foucault ventured into criticizing pyschoanalysis and Lacan in the “History of Sexuality“, Deleuze wrote to Foucault to try to reconcile their theories. But Foucault hated Deleuze’s notion of desire. Foucault told a friend “I can’t stand the word desire; even if you use it different, I can’t stop myself from thinking or feeling that desire equals lack.” But rather then starting a dialogue with Deleuze about their differences, he refused to respond to Deleuze’s letter and broke off their friendship.

It was a trying time for Foucault. The first volume of the “History of Sexuality” was not received well by Foucault’s peers. And as it turns out, it was Baudrillard’s “Forget Foucault” that caused Foucault to abandon the final two volumes of the series for 7 years.

Baudrillard’s “Forget Foucault” was the final straw, so stunning the weakened philosopher that he abandoned the entire edifice that he had planned. It was only after seven years of silence, after having thoroughly revisited its premises, that he published the second volume of his “History of Sexuality.”

Towards the end of Foucault’s life, he tried to reconcile with Deleuze but never got the chance. When Foucault fell ill, Deleuze called friends of Foucault to inquire about his conditions. An optimistic Deleuze commented “Maybe it’s nothing, Foucault will leave the hospital and come and tell us that everything is all right.” But Deleuze was wrong, Foucault would die that year in 1984.

According to Didier Eribon, one of Foucault’s most heartfelt wishes, knowing that he would not live long, was to reconcile with Deleuze. They never saw each. The fact that Daniel Defert asked Deleuze to speak at Foucault’s funeral was a sign of how much both men wanted to smooth over their differences, even beyond the seperation of death.

#12 Deleuze worked in a philosophy department headed by Foucault that lost its ability to give out diplomas

After the events of May ’68, Paris-VIII, also known as Vincennes, was created to be a refuge for radical students. A committee of 20 peoples that included Jacques Derrida and Roland Barthes set out to model Vincennes after MIT. Michel Foucault was named the head of the philosophy department. While Deleuze could not initially work at Vincennes, he later joined a staff that was comprised of Alain Badiou, Jacques Ranciere, Jean-Francois Lyotard and Judith Miller.

If you wondered what could go wrong in a department filled with radicals and communists, the answer is everything. Students tore open ceilings to see “if the police had bugged the rooms” and matters of administration were often seen as fascist coups. Department members invited friends to teach classes, many of whom would not even show up for class.

When Ranciere and Badiou decided that “not showing up” was pretty good grounds to fire these teachers, the victims immediately declared it “a Bolshevik coup and alerted Deleuze and Lyotard, who saw it as the start of a witch hunt. ‘They organized a sort of hunger strike in Deleuze’s seminar.'”

And grades? Capitalist bullshit! Judith Miller openly declared “certain collective have decided not to grade students on the basis of written workers, others have decided to give a diploma to anyone who thinks they deserve one.” If you just thought “Hey! That’s something I shouldn’t openly announce to the public”, then congratulations, you’re right. The French government swiftly declared that the Vincennes philosophy department could no longer award national diplomas.

#13 In that department, Deleuze was constantly terrorized by Alain Badiou and his troop of Maoist

It wasn’t very long after the publication of “Rhizome” that the philosophy department turned into a veritable Game of Thrones. Badiou, wary of Deleuze’s popularity, led a group of Maoists who pledged their loyalty to Badiou, whom they referred to as the “Great Helmsman.”

Badiou declared Deleuze an “enemy of the people” and penned several anti-Deleuze articles. Under the psuedonym “Georges Peyol”, Badiou penned “The Fascism of the Potato,” because if I know anything about resisting fascism, it usually involves declaring enemies of the people and creating a cult of personality around yourself.

Speaking of fascism, Badiou and his gang of merry Maoist decided to stage invasions of Deleuze’s class room.

At the height of the conflict, Badious “men” would prevent Deleuze from finishing his seminar, he would put his hat back on to his head to indicate surrender. Badiou himself would occasionally turn up at Deleuze’s seminar to interrupt him, as he admits in the book he wrote on Deleuze in 1997.

Badiou, who is still totally not a fascist, created brigades to “monitor the political content of other classes in the philosophy department.” Deleuze responded to most interventions calmly, and would avoid conflict even when “groups of up to a dozen people bent on picking a fight would show up.”

Sometimes these brigades would show up with copies of Nietzsche to ask trick questions in an effort to embarrass Deleuze. And when that didn’t work:

Often the “brigade” would end up imposing the “Peoples Rule,” commanding the student to quit Deleuze’s classroom on the pretext of a meeting in Lecture Hall 1 or a rally in support of a workers’ struggle. Deleuze reacted calmly, pretending to agree with them and retaliating with irony.

And when that also didn’t work:

Only once did [Deleuze] get angry, when he found on his desk a tract by a “death squad” advocating suicide.”

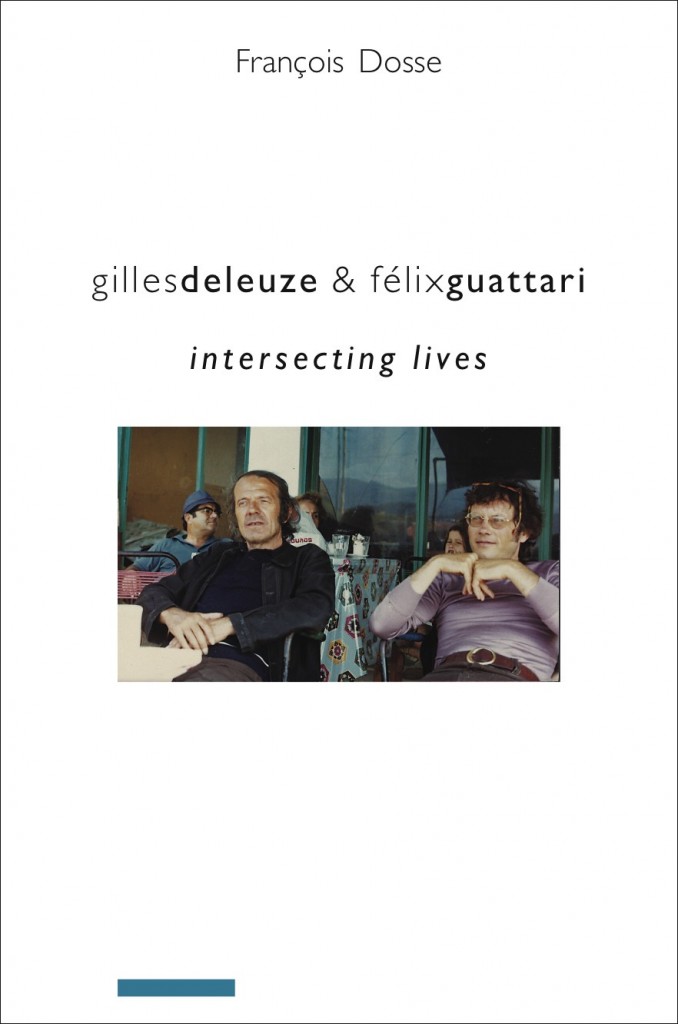

All quotes and facts are derived from the Deleuze and Guattari biography “Intersecting Lives”, unless otherwise noted.