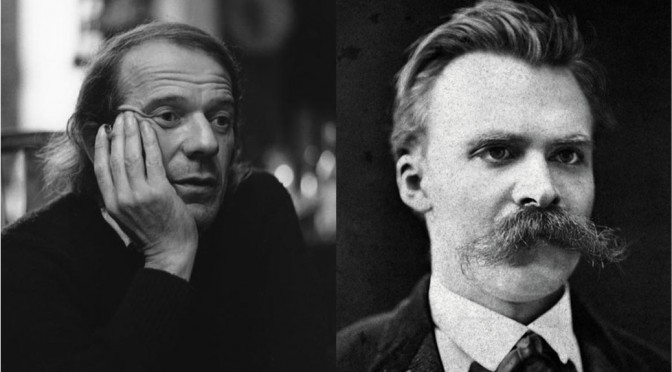

This interview, entitled “Nietzsche’s Burst of Laughter”, was published in 1967 in the French newspaper Le Nouvel Observateur on April 5. It was conducted by Guy Dumur. Posted to Reddit, the source of the translation is not cited. However, a translation of the same interview exists in “Desert Islands: and Other Texts, 1953–1974.”

Deleuze discusses the release of Nietzsche’s collected works, and the problems analyzing Nietzsche’s oeuvre. Many of Nietzsche’s works were heavily altered posthumously by his sister to make them more appealing to the German Nazi Party.

“Elizabeth Forster-Nietzsche put together an extremely harmful work that privileges many Nazi interpretations,” Deleuze notes. “She didn’t falsify the texts, but we know well enough that there are other ways to distort an author’s thinking, even if it is merely an arbitrary selection from among his papers.”

Before writing “Anti-Oedipus” with Felix Guattari, Deleuze wrote about the history of philosophy, including “Nietzsche and Philosophy.” It was the second book he ever published.

Deleuze continues to speak on the relevance of Nietzsche in contemporary France. “The reaction against oppressive structures is no longer done, for him, in the name of a ‘self’ or an ‘I,’ Deleuze says. “On the contrary, it is as though the ‘self’ and the ‘I’ were accomplices of those structures.”

Read the interview below:

Dumur: How was the new edition of Nietzsche’s Complete Philosophical Works established?

Deleuze: The problem was to reclassify the posthumous notes—the Nachlass—in accordance with the dates Nietzsche had written them, and to place them after the works with which they were contemporaneous. Some of them had been used in an abusive way after Nietzsche’s death to compose The Will to Power. So it was essential to reestablish the exact chronology. This explains why the first volume, The Gay Science, is more than half composed of previously unpublished fragments dating from 1881-1882. Our conception of Nietzsche’s thought as well as his creative process may be profoundly altered as a result. The new edition will appear simultaneously in Italy, Germany, and France. But we owe the texts to the work of two Italians, Colli and Montinari.

Dumur: How do you explain that Italians rather than Germans did the job?

Deleuze: Maybe the Germans were not in a good position to do it. They already had numerous editions, which they were fond of, despite the arbitrary organization of the notes. Also, Nietzsche’s manuscripts were in Weimar, East Germany—where the Italians were better received than any West German could have hoped to be. Finally, the Germans were undoubtedly embarrassed at having accepted the edition of The Will to Power created by Nietzsche’s sister. Elizabeth Forster-Nietzsche put together an extremely harmful work that privileges many Nazi interpretations. She didn’t falsify the texts, but we know well enough that there are other ways to distort an author’s thinking, even if it is merely an arbitrary selection from among his papers. Nietzschean concepts like those of “force” or “master” are complex enough to be betrayed by a selection such as hers.

Dumur: Will the translations be new?

Deleuze: Completely new. This is especially important for those writings toward the end (there have been some poor readings, for which Elizabeth Nietzsche and Peter Gast are responsible). The first two volumes to be published, The Gay Science and Human, All Too Human, have been translated by Pierre Klossowski and Robert Rovini. This doesn’t mean that the prior translations by Henri Albert, and by Genevieve Bianquis, were bad—not at all. But if they were determined to publish Nietzsche’s notes with his works, they had to begin from scratch and unify the terminology. On that note, interestingly enough, Nietzsche was first introduced in France not by the “right,” but by Charles Andler and Henri Albert, who represented a whole socialist tradition with anarchical colorings.

Dumur: Do you think a “return to Nietzsche” is taking place in France today? And if so, why is it?

Deleuze: It’s difficult to say. Maybe there has been a change, or maybe the change is taking place now, with respect to the modes of thought which have been so familiar to us since the Liberation. We were used to thinking dialectically, historically. Today it seems the tide has turned from dialectical thinking toward structuralism, for example, as well as other systems of thought.

Foucault insists on the importance of the techniques of interpretation. It’s possible that in the actual idea of interpretation is something which goes beyond the dialectical opposition between “knowing” and “transforming” the world. Freud is the great interpreter, so is Nietzsche, but in a different way. Nietzsche’s idea is that things and actions are already interpretations. So to interpret is to interpret interpretations, and thus to change things, “to change life.” What is clear for Nietzsche is that society cannot be an ultimate authority. The ultimate authority is creation, it is art: or rather, art represents the absence and the impossibility of an ultimate authority. From the very beginning of his work, Nietzsche posits that there exist ends “just a little higher” than those of the State, than those of society. He inserts his entire corpus in a dimension which is neither historical, even understood dialectically, nor eternal. What he calls this new dimension which operates both in time and against time is the untimely. It is in this that life as interpretation finds its source. Maybe the reason for the “return to Nietzsche” is a rediscovery of the untimely, that dimension which is distinct both from classical philosophy in its “timeless” enterprise and from dialectical philosophy in its understanding of history: a singular element of upheaval.

Dumur: Could we then say this is a return to individualism?

Deleuze: Yes, but a bizarre individualism, in which modern consciousness undoubtedly recognizes itself to some degree. Because in Nietzsche, this individualism is accompanied by a lively critique of the notions of “self” and “I.” For Nietzsche there is a kind of dissolution of the self. The reaction against oppressive structures is no longer done, for him, in the name of a “self” or an “I.” On the contrary, it is as though the “self” and the “I” were accomplices of those structures.

Must we say that the return to Nietzsche implies a kind of aestheticism, a renunciation of politics, an “individualism” as depersonalized as it is depoliticized? Maybe not. Politics, too, is in the business of interpretation. The untimely, which we just discussed, is never reducible to the political-historical element. But it happens from time to time that, at certain great moments, they coincide. When people die of hunger in India, such a disaster is political-historical. But when the people struggle for their liberation, there is always a coincidence of poetic acts and historical events or political actions, the glorious incarnation of something sublime or untimely. Such great coincidences are Nasser’s burst of laughter when he nationalized Suez, or Castro’s gestures, and that other burst of laughter, Giap’s television interview. Here we have something that reminds us of Rimbaud’s or Nietzsche’s imperatives and which puts one over on Marx—an artistic joy that comes to coincide with historical struggle. There are creators in politics, and creative movements, that are poised for a moment in history. Hitler, on the contrary, lacked to a singular degree any Nietzschean element. Hitler is not Zarathoustra. Nor is Trujillo. They represented what Nietzsche calls “the monkey of Zarathoustra.” As Nietzsche said, if one wants to be “a master,” it is not enough to come to power. More often than not it is the “slaves” who come to power, and who keep it, and who remain slaves while they keep it.

The masters according to Nietzsche are the untimely, those who create, who destroy in order to create, not to preserve. Nietzsche says that under the huge earth-shattering events are tiny silent events, which he likens to the creation of new worlds: there once again you see the presence of the poetic under the historical. In France, for instance, there are no earth-shattering events right now. They are far away, and horrible, in Vietnam. But we still have tiny imperceptible events, which maybe announce an exodus from today’s desert. Maybe the return to Nietzsche is one of those “tiny events” and already a reinterpretation of the world.