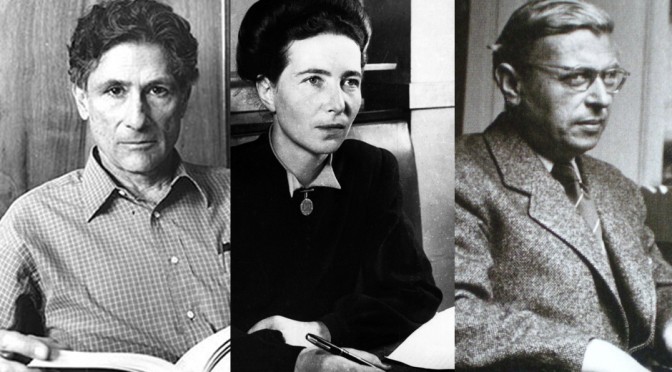

In 1979, Edward Said was invited by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir to France for a conference on Middle East peace. It was in the wake of the Camp David Accords that ended the war between Egypt and Israel, that the author of “Orientalism” and ardent supporter of the Palestinian people, was invited to contribute with other prominent thinkers.

Said offered effusive praise for Sartre when recounting his adventure, writing for the London Review of Books:

“He was never condescending or evasive, even if he was given to error and overstatement. Nearly everything he wrote is interesting for its sheer audacity, its freedom (even its freedom to be verbose) and its generosity of spirit”

But despite admiring Sartre and de Beauvoir, Said was disappointed after meeting his intellectual heroes. Upon arriving in France, Said received a mysterious note informing him that, for security reason, the proceedings were to be held in the home of Michel Foucault.

Upon arriving, Said encountered de Beauvoir, who was lecturing against chadors, a cloak worn by Iranian women that leaves only a woman’s face exposed.

Beauvoir was already there in her famous turban, lecturing anyone who would listen about her forthcoming trip to Teheran with Kate Millett, where they were planning to demonstrate against the chador; the whole idea struck me as patronising and silly, and although I was eager to hear what Beauvoir had to say, I also realised that she was quite vain and quite beyond arguing with at that moment. Besides, she left an hour or so later (just before Sartre’s arrival) and was never seen again.”

30 years later, the point of conflict between Said and de Beauvoir is still hotly debated following Western assaults on hijabs, niqabs, burqas and other traditional Muslim attire. The defense of these garments, taken on by thinkers like Saba Mahmood and Lila Abu-Lughod is often deeply indebted to Said’s work on racist Western conceptions of the East.

Said continues:

“Beauvoir had been a serious disappointment, flouncing out of the room in a cloud of opinionated babble about Islam and the veiling of women. At the time I did not regret her absence; later I was convinced she would have livened things up. Sartre’s presence, what there was of it, was strangely passive, unimpressive, affectless. He said absolutely nothing for hours on end. At lunch he sat across from me, looking disconsolate and remaining totally uncommunicative, egg and mayonnaise streaming haplessly down his face. I tried to make conversation with him, but got nowhere. He may have been deaf, but I’m not sure. In any case, he seemed to me like a haunted version of his earlier self, his proverbial ugliness, his pipe and his nondescript clothing hanging about him like so many props on a deserted stage. “

But the dissapointment for Said was in Sartre, de Beauvoir and even Foucault’s unflinching support of Israel.

Foucault “very quickly made it clear to me that he had nothing to contribute to the seminar and would be leaving directly for his daily bout of research at the Bibliothèque Nationale,” Said recounts, “I was pleased to see my book Beginnings on his bookshelves, which were brimming with a neatly arranged mass of materials, including papers and journals.”

But Said was baffled by Sartre, whose position in support of the Algerian people was not enough to invoke a similar sense of outrage over the plight of the Palestinians.

“Sartre struck me as worth the effort simply because I could not forget his position on Algeria, which as a Frenchman must have been harder to hold than a position critical of Israel. I was wrong of course.”

Later, Sartre would present comments that Said suspected was written by a colleague of his. He further recounts:

“Sure enough Sartre did have something for us: a prepared text of about two typed pages that – I write entirely on the basis of a twenty-year-old memory of the moment – praised the courage of Anwar Sadat in the most banal platitudes imaginable. I cannot recall that many words were said about the Palestinians, or about territory, or about the tragic past. Certainly no reference was made to Israeli settler-colonialism, similar in many ways to French practice in Algeria…I was quite shattered to discover that this intellectual hero had succumbed in his later years to such a reactionary mentor, and that on the subject of Palestine the former warrior on behalf of the oppressed had nothing to offer beyond the most conventional, journalistic praise for an already well-celebrated Egyptian leader. For the rest of that day Sartre resumed his silence, and the proceedings continued as before. I recalled an apocryphal story in which twenty years earlier Sartre had travelled to Rome to meet Fanon (then dying of leukemia) and harangued him about the dramas of Algeria for (it was claimed) 16 non-stop hours, until Simone made him desist. Gone for ever was that Sartre.”

Frantz Fanon was friends with both Sartre and de Beauvoir, and Sartre would write the preface to Fanon’s “The Wretched of the Earth.”

“All I do know is that as a very old man he seemed pretty much the same as he had been when somewhat younger: a bitter disappointment to every (non-Algerian) Arab who admired him,” Said concludes.

Read the full diary from Said here.