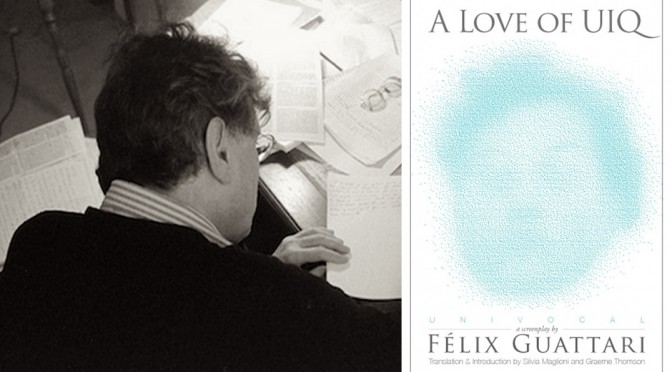

In 1987, Felix Guattari approached France’s National Center of Cinematography in hopes that they would fund production of his film, entitled “A Love of UIQ.” Guattari, who had no experience in film, attached a CV, rather than a filmography, to his application. It detailed, among other things, that he had been under police investigation during the Algerian War and his involvement in the 1977 radical uprisings in Italy.

“A Love of UIQ,” is the story of humanity’s first contact with an entity known as the “Infra-Quark Universe,” UIQ for short, a being that relays communications via the chloroplasts of tiny phytoplankton. At first glance, it’s more or less a plot line from Star Trek, minus the space stuff.

Spoilers ahead:

Under hazy circumstances an American journalist rescues a German biologist named Axel. As the duo evades the authorities, they come across Janice, a sexually liberated 20-something who brings the two to her commune of squatters in an abandoned factory.

There, we learn that the disruption of TV and radio signals was the result of Axel’s experiments and he had barely escaped after the police stormed his lab. Axel builds a new lab and, with the help of the other squatters, finally makes contact with the being named UIQ. An intelligence that exists on a subatomic scale (hence, infra-quark), UIQ inhabits a computer screen and is able to exert its power over not only machines, but nature.

Janice teaches UIQ about the world of humanity, and UIQ falls in love with her. Wishing to marry Janice, UIQ has a child murder a passed-out drunk so that he may possess his body. UIQ, now existing as both the corporeal Bruno and UIQ, pursues Janice and when all else fails, decides to smite humanity with rapid and erratic mutations that endow its victims with the characteristics of other animals such as dogs, lizards, flys, and so on. Only after Janice agrees to have UIQ physically implanted inside her brain does the terror stop. Afterward, Janice wanders aimlessly, modulating between a female and male voice, speaking nonsense . The book ends with the strange, monotonous voice emanating from her body: “Might he give her back her death at least.”

End spoilers.

Considering his dense prose, “A Love of UIQ” is surprisingly accessible. Unlike his other work, Guattari had hoped that “A Love of UIQ” could reach the masses as a major Hollywood Film. He collaborated with American filmmaker Robert Kramer on the film and approached one of the producers of “Taxi Driver,” Michael Phillips, to work on the film.

“Cinema is an extraordinary instrument for producing subjectivity,” Guattari writes in the preamble to the script. “A Love of UIQ…is neither an autobiographical nor an essay film, though it closely relates to my conception of psychoanalysis.”

That Guattari chose the genre of science fiction should be of no surprise. Both the genre, and his philosophy, imagine a world untethered from current realities. The film explores both the promise, and danger, of new forms of subjectivity.

As translators Silvia Maglioni and Graeme Thomson note:

Of course the idea that a militant thinker like Guattari might persuade a government funding body to bankroll a science fiction movie, a film that Guattari, with no previous filmmaking experience…was proposing to direct himself, was surely in itself science fiction

As Frieze Magazine notes, following the films rejection from American and French studios,

Guattari abandoned the script in 1987; it languished in the IMEC archives, a repository for the collected works of numerous French academics. The philosopher so fascinated by the revolutionary potential of cinema returned exclusively to publishing and working at La Borde until his death in 1992.

Maybe Netflix can resurrect the film from the dead. Until then, we’ll have to settle for the script.

“A Love of UIQ” is available March, 2016 from Univocal.