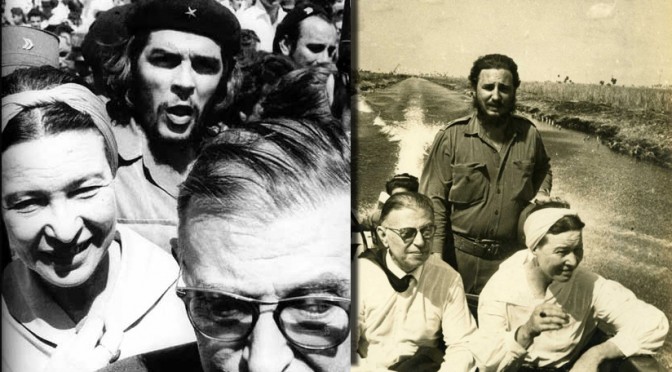

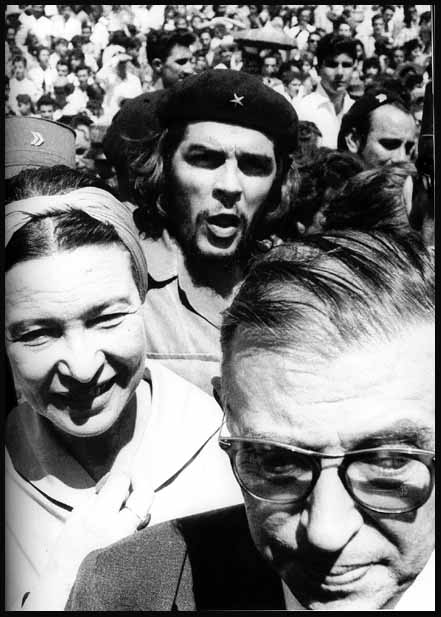

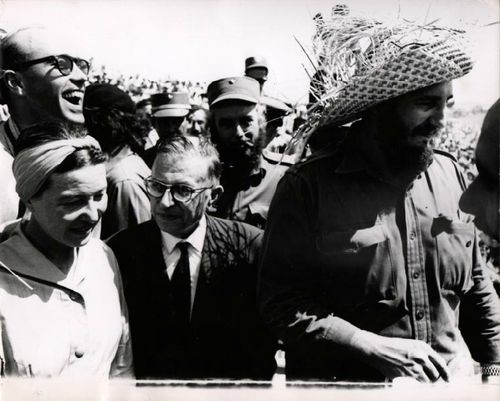

When people recount the lives of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, hanging out in boats with Fidel Castro and getting photobombed by Che Guevara seem to rarely make the cut.

In 1960, during the afterglow of the Cuban revolution, the famous feminist philosophers took a trip with her long-time companion Sartre to Havana. They were part of a larger flock of leftist intellectuals who were invited to Cuba to attend cultural congresses.

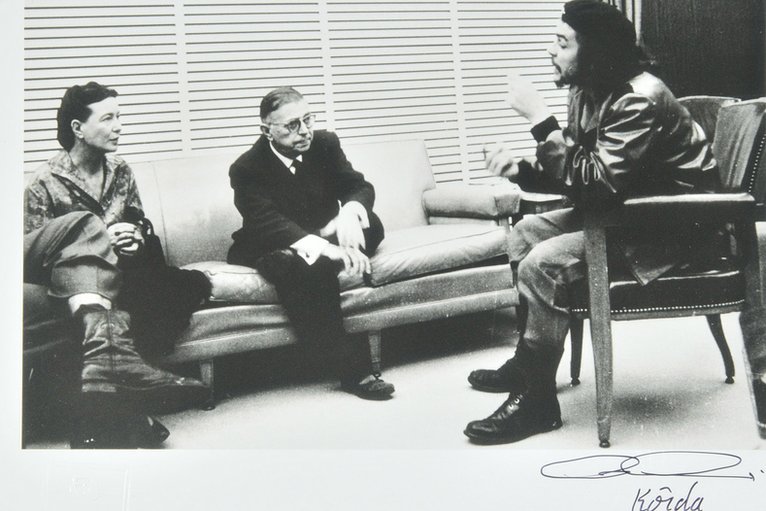

When they arrived in February, they met with Che Guevara and talked for hours, the biography “Che” recounts.

Sartre reported on his visit in 16 articles to the French newspaper France-Soir entitled “Storm Over Sugar.”

Guevara developed an interest in philosophy after taking a philosophy class in his teens. Soon afterward, according to “Che,” he wrote his own philosophical dictionary that spanned 165 pages. After studying Freud, Marx, Engels and Lenin, Guevara began reading the literature of Kafka, Camus, Sartre and Faulkner.

“It must have been a very gratifying experience for [Che], playing host to the philosopher whose works he had grown up reading. For his part, Sartre came away extremely impressed. When Che died, Sartre wrote that he was ‘not only an intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age.'”

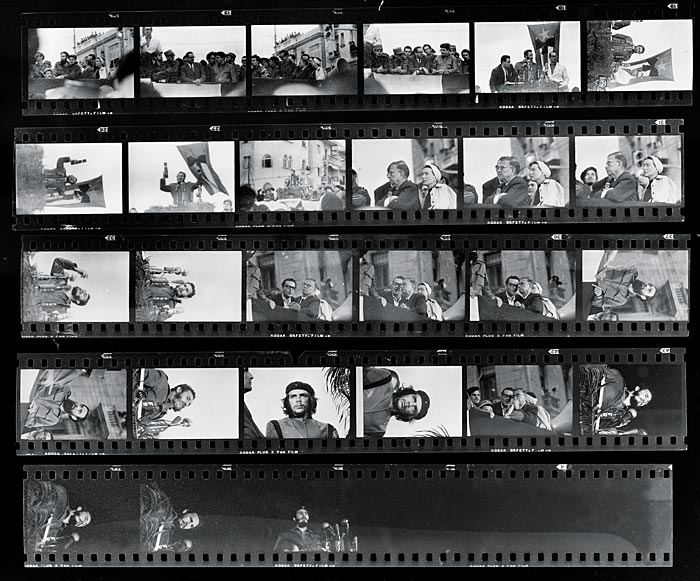

The photos were taken by Cuban photographer Alberto Korda. Korda is often known for his iconic photo of Che that has since become the basis for the image plastered on t-shirts, buttons and posters. Incidentally, that image shares the same reel of film as many images featuring Sartre and de Beauvoir in Havana.

After a speech from Fidel Castro recounting the La Coubre incident,

After a speech from Fidel Castro recounting the La Coubre incident,

“Sartre and de Beauvoir walked through the streets of Old Havana, where they saw a public fund-raising campaign already under way for a new consignment of arms. De Beauvoir was bewitched by the sensual, fervent mood. ‘Young women stood selling fruit juice and snacks to raise money for the State,’ she wrote later.”

De Beauvoir later wrote:

“Well-known performers danced or sang in the squares to swell the fund; pretty girls in their carnival fancy dresses, led by a band, went through the streets making collections. ‘It’s the honeymoon of the Revolution,’ Sartre said to me. No machinery, no bureaucracy, but a direct contact between leaders and people, and a mass of seething and slightly confused hopes. It wouldn’t last forever, but it was a comforting sight. For the first time in our lives, we were witnessing happiness that had been attained by violence.”

Later that year in October, Sartre and de Beauvoir returned to Cuba, but were somewhat disappointed. “Che” further recounts:

“Fidel invited Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir to visit Cuba again, and they did, but this time they weren’t so entranced. ‘Havana had changed; no more nightclubs, no more gambling, and more more American tourists; in the half empty Nacional Hotel, some very young members of the militia, boys and girls, were holding a conference. On every side, in the streets, the militia was drilling,’ de Beauvoir wrote. The atmosphere was tense with rumors of invasion, and a notable air of repressive uniformity was seeping into Cuban life. When Sartre and de Beauvoir asked workers at a clothing mill how they lives had benefited from the revolution, a union leader quickly stepped forward to speak on their behalf, parroting the government’s dogma. “

Later in life, Sartre’s relation with Castro soured. As “Sartre Against Stalinism” notes:

“In 1971, after Sartre had taken up the case of the imprisoned Cuban poet Herberto Padilla, he found himself being denounced by his erstwhile comrade Castro as being among the “bourgeois liberal gentleman…two bit agents of colonialism…agents of the CIA and intelligence services of imperialism” who had dared to criticize Cuba. Sartre responded with a plea to Castro to ‘spare Cuba the dogmatic obscurantism, the cultural xenophobia and the repressive system which Stalinism imposed in the socialist countries.

But at least they got to hang out in this rad helicopter.