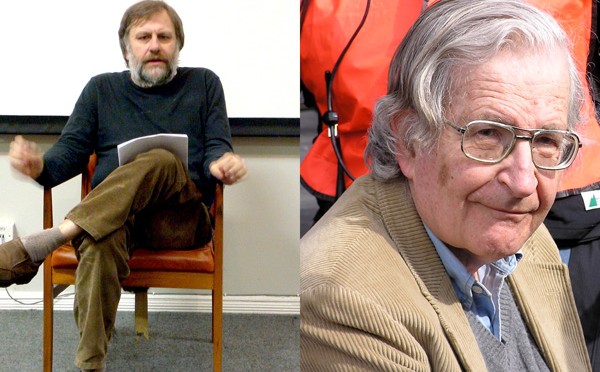

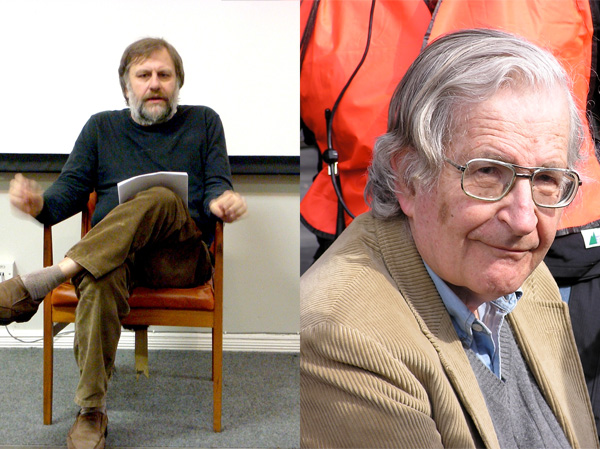

In an interview published today, Christopher Helali from Pax Marxista talks with Noam Chomsky about Marxism and revolution before ending on the topic of Slavoj Zizek. But was the interview a ruse to get Chomsky to respond to Zizek in the first place?

Chomsky has been in an intellectual pissing match with Slavoj Zizek for some time now, calling him out for fabrications and claiming his theories were nonsense in a December 2012 interview.

As many have noted, Chomsky’s blanket rejection of critical theory as nonsense is getting suspiciously repetitive. There is, to be fair, a real debate to be had about obscurantism in academia and and the relation of theory and reality. That analysis has all been lacking from the Chomsky-Zizek debate. For a man who spends most of his time unfurling the lies told by US media with counterfactuals, it’s a little surprising to see Chomsky avoid any real analysis of Zizek’s theories.

When asked to comment on Zizek explicitly, Chomsky pulls out his old criticism of the Slovenian philosopher. At the end of the interview, the interviewer asks Chomsky to respond to a 2009 comment Zizek made about Chomsky in the New Statesmen.

CH: Slavoj Žižek, in an interview to the New Statesman in 2009 said, and I quote: “My friend told me Chomsky said something very sad. He said that today we don’t need theory. All we need to do is tell people, empirically, what is going on. Here, I violently disagree: facts are facts, and they are precious, but they can work in this way or that. Facts alone are not enough. You have to change the ideological background…I’m sorry…I’m an old-fashioned continental European. Theory is sacred and we need it more than ever.” How would you respond to Zizek’s claim?

NC: First of all, I quite agree that just spewing out facts means nothing. In our discussion here we haven’t just been spewing out facts, it’s within a framework, a frame of understanding, principles and so on. The European intellectuals he is talking about have a concept of theory, which in my view, is largely divorced from facts and from theory, in any serious sense of the notion. It’s mostly big, complicated words that may be fun for intellectuals to throw around to each other but most of it, I think, is gibberish to tell you the honest truth. It’s not theory in any sense that I understand and I have been involved most of my life in the sciences where there are theories and so on. So sure, if you can find a theory that has some real principles which are of some interest and you can draw conclusions from them which you can apply to interpreting the actual world around you then sure, that’s wonderful. If there are such theories, I am happy to see them. I don’t find them when I read Paris Post-Modernist talk. What I see is intellectuals interacting with one another in ways which are incomprehensible to the public and, to be frank, incomprehensible to me. So sure, let’s have theories that have some intellectual content, some consequences, can be refined, change and lead us to better understanding.

Chomsky is, for the most part, repeating nearly verbatim what he’s been saying about critical theory for years. In short, it’s a man claiming “What’s going on, this hurts my brain!?!?!” who incidentally studies the “super easy to understand” field of linguistics.

But despite Chomsky’s refusal to do so, there are real points of contention to be had with Zizek. Does Chomsky properly address ideology? Is there any positive political usage to Zizek’s ideology? Are toilets really the most effective vehicles for class struggle? And did Chomsky accidentally answer some of these questions?

Reading this interview, before the name “Zizek” is actually uttered, I became immediately suspicious. Helali begins by asking Chomsky about the revival of “violent revolutionary praxis,” among “some theorists” to which he responds:

So again should we take our guns, go out in the street and start destroying Chase Manhattan bank. Well if you want to get killed in five minutes that’s a good suggestion. Other than that it has absolutely nothing to do with the world so there is not any point in even discussing it. I think it is a crazy idea myself, but quite apart from that it’s a bit like asking should we climb on an asteroid and attack the earth? Oh okay, maybe I don’t think it’s a good idea but why talk about it?

The interviewer continues to prod Chomsky on the Jacobins, revolutionary terror, and so on and so on. Is Chomsky being baited into responding to Ziek? Zizek has set out a (arguably) coherent framework on political violence, after all. And then the interviewer finally reveals that this was all probably about Zizek anyway.

CH: There was a recent article in January 2013 by Alan Johnston, writing for the telegraph and he accused Žižek of being a left-fascist, promulgating this view of totalitarianism and violence that is justified within the left tradition and something that we should reclaim in the twenty first century. How does this fascination with violence, terror and hegemony stem from the radical left tradition? Do you think that it’s a part of it or is it some offshoot?

NC: You know, there are a lot of radical left traditions. The ones that made any sense, in my view, were not committed to violence except in self defense. So, if you manage to carry forward significant changes and progressive changes, maybe radical, institutional changes, and you start to function and there is an attack on them by former centers of power, by outside powers and so on, then you defend yourself. As I said, I am not a pure pacifist; I don’t think you should stop defending yourself when you are under attack, but under very special circumstances. The idea of overthrowing existing forces by violence is a very questionable one for pretty good reasons I think. People who talk about revolution, it’s easy to talk about, but if you want a revolution, meaning a significant change in institutions that’s going to carry us forward, rather than backwards, then it has to meet a couple of conditions. One condition is it has to have dedicated support by a large majority of the population. People who have come to realize that the just goals that they are trying to attain cannot be attained within the existing institutional structure because they will be beaten back by force. If a lot of people come to that realization then they might say well we’ll go beyond the, what’s called reformism, the effort to introduce changes within the institutions that exist. At that point the questions at least arise. But we are so remote from that point that I don’t even see any point speculating about it and we may never get there. Maybe Marx is right that within parliamentary democracies you can use the institutions themselves to go to a sharp institutional change. In fact, I think there is some evidence for that. So for example, in the United States there are the beginnings of germs of what might be a real socialist or communist society like worker owned enterprises. It’s the beginnings of industrial democracy, you know popular democracy in all institutions. How far can it go, well you know, if it keeps going and there is violent resistance to it, then you can raise the question of using violence to defend it, but if it keeps going and it doesn’t meet violent resistance, then we will just continue it.

So Chomsky has sort of actually responded to Zizek rather than ignoring his ideas. By Ghandi logic, does that mean Zizek has won?

Updated: You can listen to the full interview below:

Read the full article at Pax Marxista.