Walter Benjamin is well known for his contributions to philosophy and cultural criticism. Many know him for “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” or more broadly, for his “Angel of History” that sees history not as a chain of events, but an ever-growing catastrophe.

Benjamin, like most modern writers, had to take on side gigs. And since he lived and worked in early 20th century Berlin, radio provided ample work for the Frankfurt School theorist. He found himself writing on a variety of topics for age groups of all ages, including children and adolescents.

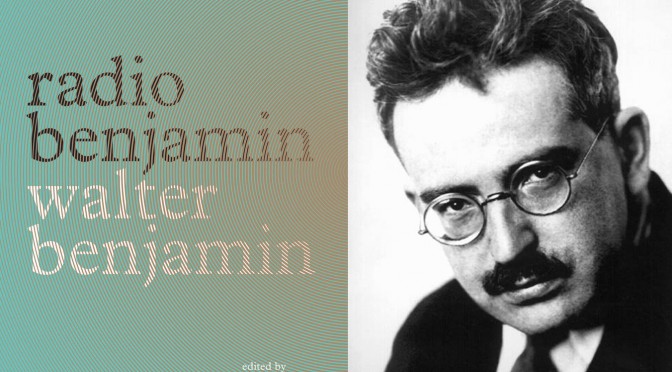

For the first time ever in English, many of these radio transcripts are now available in the newly published “Radio Benjamin.”

Between 1927 to 1933 Benjamin wrote and delivered over 80 broadcasts, according to the book’s introduction.

Benjamin’s radio plays for children, left behind after he escaped Germany in 1940, survived only by chance. The typescripts in Benjamin’s apartments were seized by the Gestapo and only escaped destruction by bureaucratic error. They weren’t published in German until 1985.

Most of Benjamin’s plays, youth hours and adult segments were ostensibly looked down upon by the author.

But there were rare moments where Benjamin refused to castigate his own radio work. Such is the case with “Much Ado About Kasper,” a radio play about an iconic German children’s character who is asked to speak on the radio.

The broadcasts in “Radio Benjamin” can be broken up into Benjamin’s “Youth Hour,” his children’s radio plays, and the “adult” stuff which consists of talks, dialogues and plays.

Benjamin’s “Youth Hour” is perhaps the most fascinating. Broadcast on Radio Berlin and Southwest German Radio from 1929 to 1932, Benjamin plays the role of a German Ira Glass for teens. In many, Benjamin subtly combats classism as it pervaded 1920s Germany. In “Berlin Dialect,” Benjamin celebrates “Berlinish,” a crude dialect of the working class that was ditched as Berliners sought to become more “refined.”

“Berlinish is a language that comes from work. It developed not from writers or scholars, but rather from the locker room and the card table, on the bus and at the pawn shop, at sporting arenas and in factories. Berlinish is a language of people who have no time, who often must communicate by using only the slightest hint, glance or half-word… Special ways of speaking always arise among such people, which you yourselves have a perfect example of in the classroom… Berlinish today is one of the most beautiful and most precise expressions of this frenzied pace of life.”

Other youth hours go on to criticize “Rental Barracks,” (the German equivalent of a tenement building), explaining to Berlin youth “what is at stake in the great battle against the rental barracks, which has been waged by Greater Berlin since 1925.”

In another, Benjamin describes the differences between “old,” and “new” Berlin, providing incredible insight into how early 20th century Berlin viewed it’s already archaic antecedent. He explains the old trade of “market women,” and their lower-class counterpart, the hawker. Hawkers were often driven to sell by economic necessity, but didn’t have the same privileges to sell the “best” goods as market women. Often viewed as crude, Benjamin celebrates the sharp tongue of Berlin’s street vendors:

“To spew insults straight from the heart, and with such perseverance, is indeed a great talent, one reserved for a privileged few. It requires not only a high degree of crassness and a healthy lung, but also a large vocabulary and, not least of all, great wit.”

Other subjects of Benjamin’s Youth Hour included factories, robber brands, witch trials and American bootleggers.

The one play that will likely spur the most interest from academics is the aforementioned “Much Ado About Kasper.” The popular German children’s figure is asked to speak on the radio, and is chased down by a radio host after refusing. Kasper manages to escape, but as the story ends it is revealed that he was on the radio all along – a microphone was hidden in his room. The theme of surveillance, although neatly packaged for a young audience, resonates today.

The Verdict

I should note that I consider myself an unabashed weirdo, who likes to read and do weird things, such as running a website about critical theory in my free time. As such, “NPR for Weirdos” is a phrase denoting absolute praise.

Readers who find themselves fascinated by the letters and notes of their favorite theorist will find a similar point of interest. Similarly, history aficionados will appreciate the first-hand look into not only radio transcripts from early 20th century Berlin, but genuinely interesting stories of contemporary events as told by one of critical theory’s greatest minds.

Buy it here.