The people of Marinaleda don’t take activism lightly. They’ve occupied airports, train stations, government buildings, farms and palaces. They’ve staged hunger strikes, blocked roads, and set up pickets. And when feeling a little ambitious, you can even count on them to raid supermarkets and donate the stolen goods to food pantries.

There’s a lot of ways to describe the left today, but “hopeful” is rarely one of them. In the United States the collapse of the Occupy movement and lack of an alternative to the status quo has many Marxists and radicals in a new-found malaise.

Yet when the inevitable question of “what is there to do?” is raised, few radicals have any clear answers. And that’s somewhat surprising. Despite the “big” failures of 20th century Communism, the 21st century boasts plenty of smaller, enduring victories against the neoliberal order.

Marinaleda is one of those victories.

We’ve all, at this point, heard of the Zapatistas. Of course, a model of society that works for the indigenous people of the Lacandan jungle doesn’t easily translate to urban metropolises, or even industrial agrarian areas.

But few of us have heard of Marinaleda, a small town tucked away in Spain’s Andalusia region.

They are led by their charismatic mayor, Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo, who has held the position since 1979. “I have never belonged to the Communist Party of the hammer and sickle,” Gordillo notes, “but I am a communist.”

The core of Marinaleda’s communist ethic is a 1,200 hectare farm that was won through a decade of occupations and hunger strikes from the Duke of Infantado. The Duke’s property was just one of many instances in Spain of vast estates with arable land fenced off from the area’s surrounding, usually starving, population.

Here in America, we are quickly infuriated that 1% of the population owns 39% of the world’s total wealth. In Andalusia, 2% of the families owned 50% of the land. Hancox notes Gordillo’s rationale for targeting the Duke’s land, “he was the one who had the most!”

Villagers would walk 10 miles, every day, to occupy the Duke’s land. They were routinely evicted by the police everyday around 6 or 7 PM. They would leave, peacefully, only to return the next day. In 1985, the people of Marinaleda did this everyday for a month, Hancox notes. It was at the height of the summer heat and they only took Sunday off to rest. When all was said and done, the Duke’s land had been occupied 100 times.

In 1991, the people of Marinaleda won. The Andalusian government compensated the Duke with an undisclosed sum, and gave it for the people of Marinaleda. They planted the Duke’s land, which previously grew non-labor intensive crops like sunflowers, with labor intensive crops like olive trees. The logic was simple: the more labor required, the more jobs would be created. So once the olive trees were grown, an already labor intensive process, they then had to be processed into oil. That would require a processing plant, and the employment of more workers. As Hancox notes, there are no profits because “any surplus is reinvested to create more jobs.” Marinaleda has an unemployment rate of 5%. Spain, by constrast, has an unemployment rate of 27%.

Hancox details his visit to the cooperatively run farm:

‘Este cortijo es para los jornaleros en paro de Marinaleda’ (this farm is for the unemployed labourers of Marinaleda) was written in massive capital letters along one stretch of wall, punctuated with a painting of the village’s iconic tricolour flag. On the other side was a giant socialist-realist painting of two fifteen-foot tall jornaleros emerging proudly, tired, from their work in the fields, with TIERRA UTOPIA written underneath.

A family lives on the farm as caretakers, running the day-to-day operations: they are neither bosses nor owners – this is a co-operative, my guide stressed. This is the co-operative, in fact: the symbolic and actual cornerstone of Marinaleda’s utopian achievement – a 1,200 hectare farm won through thirteen years of relentless struggle.

The farm, known as El Humoso, sells its products internationally. Fair-trade and “socially aware” brands often get a bad rap by critical theorists. But El Humoso makes a compelling counterpoint to the likes of Starbucks and Tom’s Shoes. “Know that when you consume any product from our co-operative, you are helping to create employment and social justice,” Gordillo tells Hancox.

The logic is compelling. “Marinaleda exists in a capitalist world,” Hancox explains “but proving that ‘we can work for reasons other than money’ is, for Sanchez Gordillo, an act of subversion of capitalism itself.”

And even for a man in power, Gordillo has a streak of anti-authoritarianism. Marinaleda, surprisingly, has no police. They didn’t abolish the police force, or violently expel its officers. Marinaleda had one police officer. When that officer retired, they never hired a replacement. Now, Gordillo has been known to chase down delinquent youths on his own and speak to their families. Surprisingly, it seems to work out.

And all the occupying and “redistribution” hasn’t gone without national attention. At one point, H&M planned a Gordillo shirt, before quickly pulling the design due to popular outrage.

For their supermarket raids, hundreds of protesters would show up in support, but only a few would go in. There, according to Hancox, they would fill 10 or so carts with food and leave without paying. Gordilla, no stranger to using the press and spectacles to his advantage, calls this sort of action “propaganda of the deed.”

“Pulling a Gordillo” even became a thing. At the height of the economic crisis in Spain, the hashtag #HazteUnGordillo (Pulling a Gordillo) was utilized by activist shoplifters. Despite some institutional outrage to Gordillo’s action, the general public was mostly supportive.

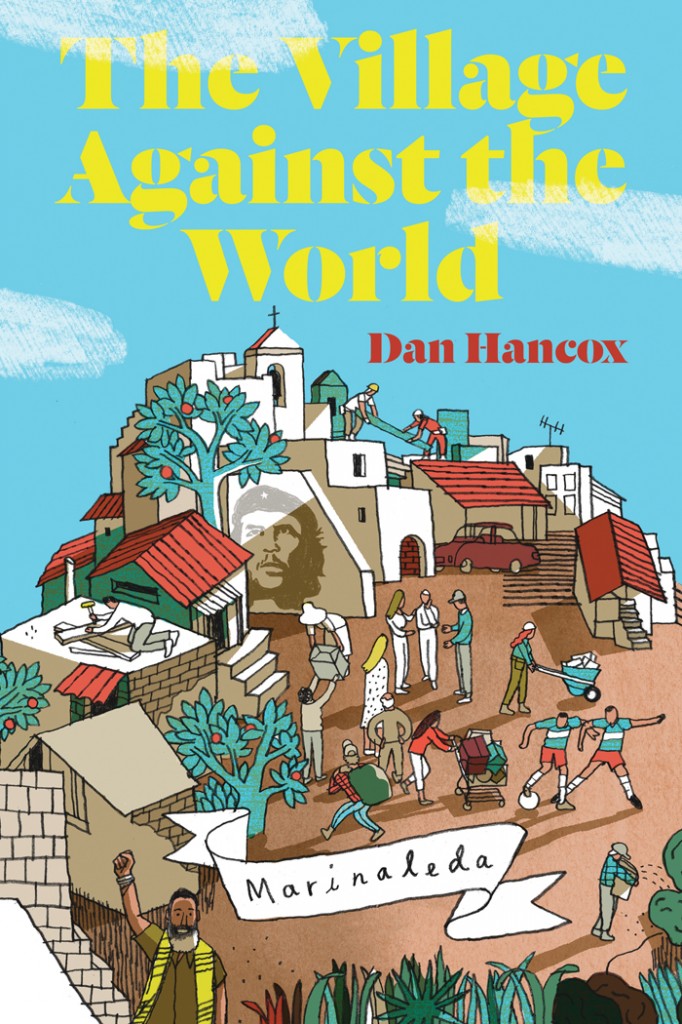

The Book

Dan Hancox’s “The Village Against the World” is, for lack of a better word, awesome. Readers won’t find a theoretically vigorous defense of Marinaleda’s politics, or criticism. Rather, Hancox’s book reads like something one might find on the New York Times best-seller list if it weren’t for its subject matter: the anti-authoritarian shenanigans of a Communist village and it’s Robin Hood mayor.

It’s a must-read for anyone interested in radical movements like Occupy Wall Street or the Zapatistas.

Buy the book here.