Nomos Journal, a free online journal dedicated to “the intersection between contemporary expressions of religion and popular culture” published an article earlier this month that argues that the music of psychedelic rocker’s Tool is, well, awesomely political.

The article, “Tool and the Dionysian Future of Music: A Pop Analysis,” is written by Sam Mickey, an adjunct professor in Theology and Religious Studies at the University of San Franscisco.

Tool is a pretty awesome rock band that is responsible for that song “Schism” that played about 5,000 times a day on every alternative rock radio station. You know, the “I know the pieces fit because I watched them fall away” song. Even great artists can get really fucking annoying after hearing that line about 20,000 times a week.

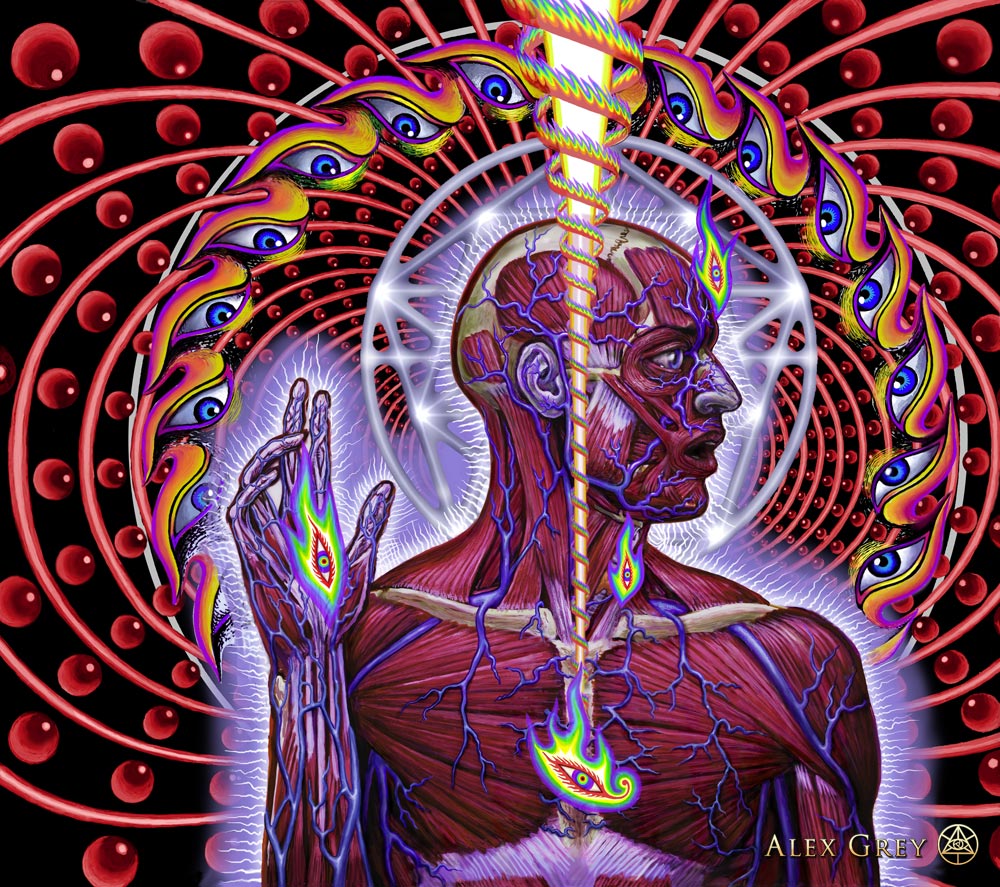

Mickey argues that “Tool’s music fulfills what Nietzsche, in Ecce Homo, calls his “tremendous hope” for “a Dionysian future of music.” Fair enough. Tool has notably used the LCD-inspired artwork of Alex Grey, and that’s pretty spiritual and shit.

Then the author talks about the importance of “pop analysis”. Apparently, Deleuze and Guattari talk about it when they’re not talking about Judge Schreber’s solar anus.

Pop analysis is a method for analyzing expressions or events that elude authoritative and proper standards. It is a method for analyzing that which escapes the majority. What Deleuze and Guattari call “pop” (“pop music, pop philosophy, pop writing”) is an “escape for language, for music, for writing,” an emancipatory gesture that makes use of the “polylingualism” of minorities and multiplicities to resist the “oppressive quality” of any regime of signs that aims to be “an official language” or “a master of the signifier.”5

…Pop subverts the status quo by becoming different. Deleuze articulates a guiding principle of pop analysis when he describes a cosmos in which “everything bathes in its difference.”6 Pop analysis traces those differences, crossing boundaries of academic disciplines and opening them up to pop languages. This methodological approach honors the creative and emancipatory power of popular culture and pop art, while also criticizing the use of cliché.

And that’s good because we can all become minoritarian or something:

As the pop analysis developed by Deleuze and Guattari suggests, becoming heterogeneous and minoritarian is the only way to effectively escape the master signifiers and major identities that dominate music, and that is precisely what pop music and pop culture accomplish.

Mickey elaborates on this whole breaking boundaries business:

Tool’s music opens possibilities for becoming different, intensifying one’s existence so as to facilitate healing for the microcosm and macrocosm of self and world. Furthermore, these religious aspects of Tool’s music can be described as Dionysian, particularly insofar as they revolve around altered and intensified states of consciousness and a non-rational impulse that undoes the subordination of rhythm to discourse (lyrics and vocal melody). The idea of Dionysian music warrants some elaboration, not only to help develop a pop analysis of the religious elements of Tool’s music, but to show how Tool expresses a boundary-dissolving impulse characteristic of the history of rock music and of pop music in general.

While I’m no expert on Deleuze, I’m pretty sure Mickey is wrong. Sure, dropping acid and writing music can break the “coding” of shitty music by being different. But if you want to talk about escaping master signifiers and becoming minoritarian without talking about the ways in which capitalism is constantly de- and reterritorializing things, well, the picture speaks for itself.