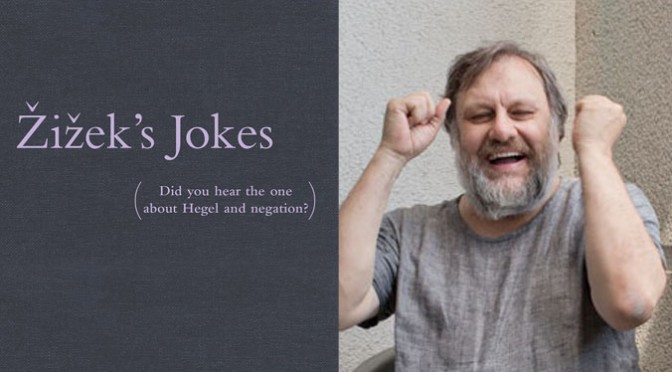

Published in March, 2014, “Zizek’s Jokes” is a small book that claims to have captured the entirety of Slavoj Zizek’s published jokes in English, variations and all.

Some of the jokes provide hilarious insight into Hegelian dialectics, Lacanian psychoanalysis or ideology. Others are just funny, and most are somewhat offensive – a characteristic Zizek admittedly doesn’t care to correct.

Here are 10 of our favorites.

#1 There is an old Jewish joke, loved by Derrida…

about a group of Jews in a synagogue publicly admitting their nullity in the eyes of God. First, a rabbi stands up and says: “O God, I know I am worthless. I am nothing!” After he has finished, a rich businessman stands up and says, beating himself on the chest: “O God, I am also worthless, obsessed with material wealth. I am nothing!” After this spectacle, a poor ordinary Jew also stands up and also proclaims: “O God, I am nothing.” The rich businessman kicks the rabbi and whispers in his ear with scorn: “What insolence! Who is that guy who dares to claim that he is nothing too!”

#2 One can well imagine a truly obscene version of the “aristocrats” joke…

that easily beats all the vulgarity of family members vomiting, shitting, fornicating, and humiliating each other in all possible ways: when asked to perform, they give the manager a short course in Hegelian thought, debating the true meaning of the negativity, of sublation, of absolute knowing, etc., and, when the surprised manager asks them what is the name of the weird show, they enthusiastically reply: “The Aristocrats!” Indeed, to paraphrase Brecht’s quote “What is the robbing of a bank compared to the founding of a bank?”: what is the disturbing shock of family members shitting into one another’s mouth compared to the shock of a proper dialectical reversal? So, perhaps, one should turn the title of the joke around— the family comes to the manager of a night club specialized in hard-core performances, performs its Hegelian dialogue, and, when asked what is the title of their strange performance, enthusiastically exclaims: “The Perverts!”

#3 The logic of the Hegelian triad can be perfectly rendered by the three versions of the relationship between sex and migraines…

We begin with the classic scene: a man wants sex with his wife, and she replies: “Sorry, darling, I have a terrible migraine, I can’t do it now!” This starting position is then negated/inverted with the rise of feminist liberation—it is the wife who now demands sex and the poor tired man who replies: “Sorry, darling, I have a terrible migraine …” In the concluding moment of the negation of negation that again inverts the entire logic, this time making the argument against into an argument for, the wife claims: “Darling, I have a terrible migraine, so let’s have some sex to refresh me!” And one can even imagine a rather depressive moment of radical negativity between the second and the third versions: the husband and the wife both have migraines and agree to just have a quiet cup of tea.

#4 When the Turkish Communist writer Panait Istrati visited the Soviet Union in the mid- 1930s, the time of the big purges…

and show trials, a Soviet apologist trying to convince him about the need for violence against the enemies evoked the proverb “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs,” to which Istrati tersely replied: “All right. I can see the broken eggs. Where’s this omelet of yours?

” We should say the same about the austerity measures imposed by IMF: the Greeks would have the full right to say, “OK, we are breaking our eggs for all of Europe, but where’s the omelet you are promising us?”

#5 The reason I find Badiou problematic is…

that, for me, something is wrong with the very notion that one can excessively “enforce” a truth: one is almost tempted to apply the logic of the joke quoted by Lacan: “My fiancée is never late for an appointment, because the moment she is late, she is no longer my fiancée.” A Truth is never enforced, because the moment fidelity to Truth functions as an excessive enforcement, we are no longer dealing with a Truth, with fidelity to a Truth-Event

#6 For decades, a classic joke has been circulating among Lacanians…

to exemplify the key role of the Other’s knowledge: a man who believes himself to be a kernel of grain is taken to a mental institution where the doctors do their best to convince him that he is not a kernel of grain but a man; however, when he is cured (convinced that he is not a kernel of grain but a man) and allowed to leave the hospital, he immediately comes back, trembling and very scared—there is a chicken outside the door, and he is afraid it will eat him. “My dear fellow,” says his doctor, “you know very well that you are not a kernel of grain but a man.” “Of course I know,” replies the patient, “but does the chicken?”

Therein resides the true stake of psychoanalytic treatment: it is not enough to convince the patient about the unconscious truth of his symptoms; the unconscious itself must be brought to assume this truth. The same holds true for the Marxian theory of commodity fetishism: we can imagine a bourgeois subject attending a Marxism course where he is taught about commodity fetishism. After the course, he comes back to his teacher, complaining that he is still the victim of commodity fetishism. The teacher tells him “But you know now how things stand, that commodities are only expressions of social relations, that there is nothing magic about them!” to which the pupil replies: “Of course I know all that, but the commodities I am dealing with seem not to know it!” This is what Lacan aimed at in his claim that the true formula of materialism is not “God doesn’t exist,” but “God is unconscious.

#7 This also makes meaningless the Christian joke…

according to which, when, in John 8:1–11, Christ says to those who want to stone the woman taken in adultery, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone!” he is immediately hit by a stone, and then shouts back: “Mother! I asked you to stay at home!”

#8 In an old joke from the defunct German Democratic Republic,…

a German worker gets a job in Siberia; aware of how all mail will be read by censors, he tells his friends: “Let’s establish a code: if a letter you will get from me is written in ordinary blue ink, it is true; if it is written in red ink, it is false.” After a month, his friends get the first letter, written in blue ink: “Everything is wonderful here: stores are full, food is abundant, apartments are large and properly heated, movie theaters show films from the West, there are many beautiful girls ready for an affair—the only thing unavailable is red ink.”

And is this not our situation till now? We have all the freedoms one wants—the only thing missing is the “red ink”: we “feel free” because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom. What this lack of red ink means is that, today, all the main terms we use to designate the present conflict —“war on terror,” “democracy and freedom,” “human rights,” etc.—are false terms, mystifying our perception of the situation instead of allowing us to think it. The task today is to give the protesters red ink.54

#9 There is an Israeli joke about Bill Clinton…

visiting Bibi Netanyahu: when Clinton sees a mysterious blue phone in Bibi’s office, he asks Bibi what it is, and Bibi answers that it allows him to dial Him up there in the sky. Upon his return to the States, the envious Clinton demands that his secret service should provide him with such a phone—at any cost. They deliver it within two weeks, and it works, but the phone bill is exorbitant—two million dollars for a one-minute talk with Him up there. So Clinton furiously calls Bibi and complains: “How can you afford such a phone, if even we, who support you financially, can’t? Is this how you spend our money?” Bibi answers calmly: “No, it’s not that—you see, for us, Jews, that call counts as a local call!”

Interestingly, in the Soviet version of the joke, God is replaced by hell: when Nixon visits Brezhnev and sees a special phone, Brezhnev explains to him that this is a link to hell; at the end of the joke, when Nixon complains about the price of the call, Brezhnev calmly answers: “For us in the Soviet Union, the call to hell counts as a local call.”56

#10 In the good old days of “actually existing Socialism,” every schoolchild was told again and again…

of how Lenin read voraciously, and of his advice to young people: “Learn, learn, and learn!” A classic joke from Socialism produces a nice subversive effect by using this motto in an unexpected context. Marx, Engels, and Lenin were each asked what they preferred, a wife or a mistress. Marx, whose attitude in intimate matters is well known to have been rather conservative, answered “A wife”; Engels, who knew how to enjoy life, answered, of course, “A mistress”; the surprise comes with Lenin, who answered “Both, wife and mistress!” Is he dedicated to a hidden pursuit of excessive sexual pleasures? No, since he quickly explains: “This way, you can tell your mistress that you’re with your wife, and your wife that you are about to visit your mistress …” “And what do you actually do?” “I go to a solitary place and learn, learn, and learn!”

You can buy the book here.