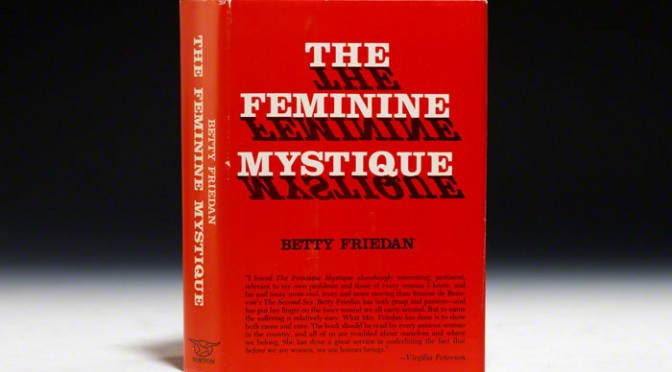

Jacobin Magazine’s Sheila Bapat is celebrating the 50th anniversary of Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” by reminding us all about how it kind of sucked in the first place.

Friedan is kind of like the Zizek of her time. She’s cool, and says some great stuff, but none of it is particularly new. She just so happens to be super popular for drawing on the work of many others in a fashionable way.

In a sea of groundbreaking feminist writing, Friedan’s book is sort of like George Clooney is to great filmmakers right now: Important. Well known. Sexy. But only scratching the surface of the talent in the field. Above all else, Friedan’s book is ideologically safe by comparison to the full body of feminist writings. She analyzed the impact of a wide range of patriarchal institutions — publishing, military, politics — on middle class women’s lives without trying to up-end any of those institutions.

In particular, Friedan’s style of feminism is marked by a focus on white, middle-class women. Bapat suggests reading Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James’s The Power of Women and the Subversion of Community instead:

Dalla Costa and James used a “feminist reading of Marx to challenge the left orthodoxy on the role of women.” They were among the first to apply Marxism to the gendered division of labor, evaluating what it means for intensive domestic labor to remain completely invisible to capital markets.

…The writers also praised the ideas of Malcolm X and other black intellectuals who tied the relationship between racial injustice and labor inequality — topics not adequately broached by Friedan.

The Atlantic also ran a pretty nice synopsis by saying: “It’s racist, and it’s classist.” Quoting bell hooks:

Friedan’s famous phrase, “the problem that has no name,” often quoted to describe the condition of women in this society, actually referred to the plight of a select group of college-educated, middle- and upper-class, married white women—housewives bored with leisure, with the home, with children, with buying products, who wanted more out of life. Friedan concludes her first chapter by stating: “We can no longer ignore that voice within women that says: ‘I want something more than my husband and my children and my house.'” That “more” she defined as careers. She did not discuss who would be called in to take care of the children and maintain the home if more women like herself were freed from their house labor and given equal access with white men to the professions. She did not speak of the needs of women without men, without children, without homes. She ignored the existence of all non-white women and poor white women. She did not tell readers whether it was more fulfilling to be a maid, a babysitter, a factory worker, a clerk, or a prostitute than to be a leisure-class housewife.

… When Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique, more than one-third of all women were in the work force. Although many women longed to be housewives, only women with leisure time and money could actually shape their identities on the model of the feminine mystique.

… From her early writing, it appears that Friedan never wondered whether or not the plight of college-educated white housewives was an adequate reference point by which to gauge the impact of sexism or sexist oppression on the lives of women in American society. Nor did she move beyond her own life experience to acquire an expanded perspective on the lives of women in the United States. I say this not to discredit her work. It remains a useful discussion of the impact of sexist discrimination on a select group of women. Examined from a different perspective, it can also be seen as a case study of narcissism, insensitivity, sentimentality, and self-indulgence, which reaches its peak when Friedan, in a chapter titled “Progressive Dehumanization,” makes a comparison between the psychological effects of isolation on white housewives and the impact of confinement on the self-concept of prisoners in Nazi concentration camps.

And homophobic. Quoting Rachel Bowlby:

Friedan sees ‘frightening implications for the future of our nation in the parasitical softening that is being passed on to the new generation of children.’ Specifically, she identifies ‘a recent increase in the overt manifestations of male homosexuality,’ and comments:

I do not think this is unrelated to the national embrace of the feminine mystique. For the feminine mystique has glorified and perpetuated the name of femininity and passive, childlike immaturity which is passed on from mother to son, as well as to daughters.

A little further on, this becomes ‘the homosexuality that is spreading like a murky smog over the American scene.’ … Male homosexuality as the end-point of the feminine mystique is not just artificial, a regrettable but accidental distortion of the reality it overlays: it is a sinister source of cultural contamination. This ‘murky smog’ is the final smut, the last ‘dirty word’ in the story of the mystique: that clean, feminine exterior is now found to hide a particularly nasty can of worms. Marketing and the mystique are together leading to ‘bearded undisciplined beatnickery’ and a ‘deterioration of the human character.’

Via Jacobin Magazine and The Atlantic